Winter grouse hunting is not a biathlon of speed, but a slow test of metabolic discipline and survival.

- Success hinges on energy conservation (caloric economy), not just ski speed or shooting prowess.

- Your clothing system is your primary survival tool; cotton is a potential death sentence due to moisture retention.

- Recognizing the subtle cognitive signs of hypothermia is more critical than spotting the bird.

Recommendation: Master your internal environment—warmth, energy, and senses—before attempting to conquer the unforgiving Nordic landscape.

The term “biathlon” conjures images of athletes racing against the clock, hearts pounding, skiing with explosive power and shooting with breathless precision. This is not the way of the Nordic winter hunter. In the vast, silent landscapes of the north, where the sun is a fleeting guest and the cold is a constant predator, the hunt is a different kind of discipline. It is less a race and more a slow, deliberate dance with the elements. Hunting capercaillie or black grouse on skis is not about speed; it’s about a profound understanding of caloric economy, resilience, and the subtle language of the wild.

Many will tell you to layer your clothing and practice your aim. This is rudimentary advice. The true challenge lies in managing the razor-thin margin between generating enough heat to stay alive and sweating enough to freeze. It’s about developing a sensory discipline that can pierce the “white deception” of a snow-covered forest and distinguish the flick of a feather from a wind-dusted branch. This is not a sport. It is a tradition steeped in survival, where the primary trophy is not the bird, but the experience of mastering oneself in the face of an indifferent wilderness.

This guide abandons the notion of a fast-paced biathlon. Instead, it offers the traditional Nordic perspective: a philosophy of hunting that prioritizes patience, environmental awareness, and deep respect for the cold. We will explore the tactics, the gear, and the critical survival knowledge that separates a successful hunt from a life-threatening ordeal. We will cover everything from interpreting a dog’s bark to recognizing the final, deceptive warmth of severe hypothermia.

This article provides a structured approach to mastering the skills required for this demanding pursuit. You will learn the core principles that govern everything from tactical decisions in the field to choosing the right destination for your current skill level, ensuring you are prepared for the profound challenge ahead.

Summary: A Deep Dive into Nordic Biathlon Hunting Skills

- Top-Calling or Stalking: Which Tactic Works for Late-Season Capercaillie?

- Elkhound or Jämthund: How to Read the Bark of a Baying Dog?

- How to Distinguish Antlers from Branches in a Whiteout?

- How to Plan a Hunt When the Sun Only Rises for 4 Hours?

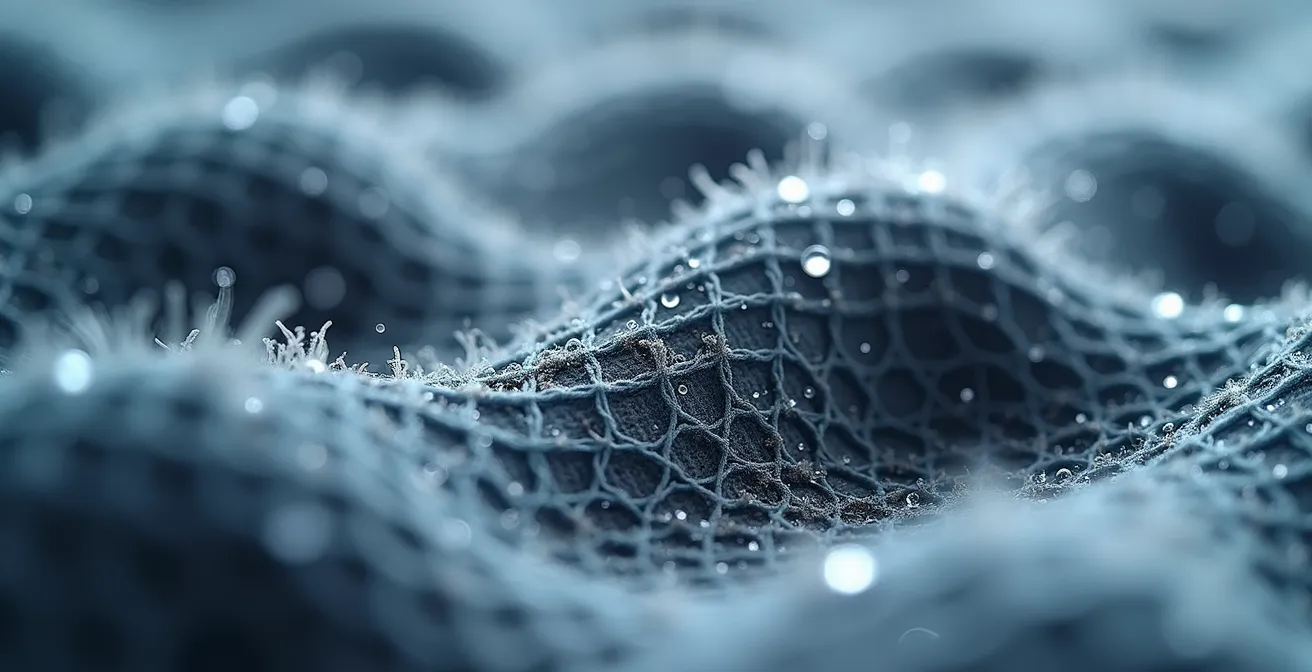

- Wool Netting vs. Solid Base: Why Is Mesh Warmer in Extreme Cold?

- Shivering vs. Confusion: Which Symptom Means You Are About to Die?

- Why Cotton Is the Enemy of the Late-Season Hunter?

- Public Land or Private Ranch: Which Destination Fits Your Skill Level?

Top-Calling or Stalking: Which Tactic Works for Late-Season Capercaillie?

In the deep cold of late season, the famed spring “lek” or mating display of the capercaillie is a distant memory. The birds are silent, conserving energy, and the tactics must adapt. Top-calling, which mimics the sounds of other birds, has limited effect. The most effective and traditional Nordic method is the slow, methodical stalk, often aided by a specialized dog. This is not a fast pursuit but an exercise in extreme patience and stealth, turning the hunt into a chess match where every move is calculated.

The process, known as “toppjakt” (top hunt), relies on finding birds as they feed on pine needles in the treetops. The hunter, clad in white camouflage and moving on wide, silent hunting skis, becomes a ghost in the landscape. The goal is to close the distance without being seen or heard. A successful stalk is a testament to one’s mastery of movement and understanding of the bird’s senses. The financial aspect also reflects this difference in difficulty; winter stalking hunts are a significant investment compared to the more accessible spring hunts, underscoring the higher level of skill and logistics required.

A successful ski-stalk is a finely tuned procedure. It combines the use of a spitz-type dog to locate and fixate the bird, with the hunter’s ability to approach undetected. The final moments are incredibly tense, often requiring movement only during the brief periods when the bird sings its short, rasping song, during which it is temporarily deaf.

- Use a spitz dog (like an Elkhound or Finnish Spitz) to range out and locate a capercaillie, chasing it up into a pine or birch tree.

- Once the dog begins its continuous “baying” bark, begin your approach on cross-country skis, using the dog’s noise to mask your own.

- Within 200-300 meters, transition to a slow, deliberate stalking mode, using every available tree and terrain feature for cover.

- If the bird is a black grouse engaged in its song, move only during the 5-6 second singing phases when it cannot hear you approach.

- Take a stable, rested shot with a high-powered rifle or combination gun before the bird takes flight.

Ultimately, stalking is the superior late-season method. It embodies the Nordic hunting ethos of patience, resilience, and a deep connection with the environment and the working dog.

Elkhound or Jämthund: How to Read the Bark of a Baying Dog?

In the silent, snow-muffled forest, the bark of your hunting dog is not just noise; it is a vital stream of information. Whether you hunt with a Norwegian Elkhound, a Finnish Spitz, or a Jämthund, understanding the nuances of its vocalizations is the key to a successful partnership. This is the silent contract between hunter and dog. A novice hears a bark; an experienced hunter hears a story unfolding in real-time. The dog’s role is to find the grouse and “tree” it, holding it in place with a continuous bark while you make your slow approach on skis.

The first signal to learn is the “find bark”—a series of excited, intermittent yaps as the dog picks up fresh scent. This is your cue to slow down and prepare. As the dog closes in and forces the bird into a tree, the barking changes. It becomes a steady, rhythmic, and hypnotic “baying bark.” This is the sound that holds the bird’s attention, fixating it on the commotion below and masking your silent, downwind approach. A steady, confident rhythm means the bird is secure and the dog is in control.

The pitch and frequency tell their own story. A high-pitched, frantic bark might mean the bird is nervous and ready to fly. A lower, more measured tone suggests a calm, settled bird. If the barking suddenly stops, it means one of two things: the bird has flown, or the dog is repositioning. If it resumes from a new location, you must adjust your stalk. If it’s followed by a series of frantic “chase barks,” you know the opportunity is lost, and the dog is in pursuit again. Learning this language transforms the hunt from a solitary effort into a collaborative dance.

It’s a skill built over years and countless hours in the forest, forging a connection that transcends spoken words and is fundamental to the Nordic hunting tradition.

How to Distinguish Antlers from Branches in a Whiteout?

The title’s mention of antlers highlights a universal challenge for the winter hunter: in a monochrome world of snow and bare trees, spotting game is an act of extreme sensory discipline. Your eyes, accustomed to color and contrast, are easily fooled. A snow-dusted branch can perfectly mimic the curve of an antler, and a grouse can appear as just another knot on a limb. The key is not to look *for* the animal, but to look for anomalies—the subtle breaks in the pattern of the forest.

First, train your eyes to see shapes, not things. Look for unnatural horizontal lines in a world of vertical trees. A grouse perched on a branch is a horizontal form that cuts against the grain of the forest. Second, look for negative space. Don’t scan the branches themselves; scan the gaps between them. An animal’s body will create a “hole” or a void where you expect to see through. In a whiteout, this is often more detectable than the animal itself. Another powerful technique is to watch for the slightest micro-movement—the turn of a head, the flick of a feather—by scanning small sectors for 30-60 seconds at a time rather than sweeping your gaze broadly.

Timing is also critical. According to wildlife biologist research, grouse in winter may only feed once or twice a day, typically near first and last light, to conserve energy. This is your prime window. During these times, also watch for puffs of steam from an animal’s breath or the dark shape of a grouse burrowing into the snow to roost for warmth. Your ears are just as important; stop frequently, cup your hands behind your ears, and listen for the soft sound of a bird scratching or the crunch of snow that betrays a larger animal’s presence.

This is not just about vision; it’s about a holistic, multi-sensory engagement with an environment that actively tries to hide its secrets.

How to Plan a Hunt When the Sun Only Rises for 4 Hours?

When daylight is a scarce commodity, time management becomes a survival skill. In the far north, a four-hour window of sunlight doesn’t mean a four-hour hunt; it means your entire schedule, including sleep, is dictated by the behavior of your quarry. Planning such a hunt is an exercise in strategy and adaptation, forcing a major disruption to your body’s natural rhythm. You don’t hunt when you feel rested; you hunt when the opportunity exists, which is often in the deep cold of pre-dawn.

The capercaillie hunt, for instance, often begins in complete darkness, around midnight or 3 AM. This allows you to be in position as the very first light filters through the trees, which is when the birds are most active. This inversion of the normal day requires a specific mindset and preparation. Sleep becomes something you grab in short, strategic bursts during the “day” (the brightest part of the 20 hours of darkness). Your planning must revolve around maximizing energy for these critical, high-exertion periods in the cold.

The following table illustrates the dramatic shift in scheduling compared to a hunt in a more temperate climate. It highlights how activities are compressed into narrow windows, governed by faint light and extreme temperatures.

| Activity | Standard Season | 4-Hour Daylight |

|---|---|---|

| Capercaillie Hunt Start | Dawn (5-6 AM) | Midnight-3 AM |

| Black Grouse Hunt | Sunrise | Just before sunrise |

| Woodcock Evening Flight | Dusk | Brief evening window |

| Temperature Range | 0 to 15°C | -10 to 15°C |

Success is not just about being in the right place at the right time, but about having the physical and mental fortitude to operate effectively when your body is screaming for rest. It is the ultimate test of a hunter’s discipline.

Wool Netting vs. Solid Base: Why Is Mesh Warmer in Extreme Cold?

In the brutal cold of a Nordic winter, your base layer is not just clothing; it is your primary defense against hypothermia. The conventional wisdom of a solid, tight-fitting base layer is challenged by a traditional Scandinavian innovation: wool netting or mesh. It seems counterintuitive—how can a shirt full of holes be warmer? The answer lies in the physics of insulation and moisture management, which are critical when managing your metabolic threshold.

The primary function of a base layer is twofold: to wick sweat away from your skin and to trap a layer of warm air. A solid base layer wicks well, but when you stop moving after a period of exertion (like a ski up a steep hill), the moisture held in the fabric can chill you rapidly. This is where mesh excels. The “holes” in the netting are not a weakness; they are its greatest strength. They create large pockets of air directly against your skin, which is then warmed by your body heat. Air is a fantastic insulator, and this trapped layer provides exceptional warmth with minimal weight.

Furthermore, the mesh design provides superior moisture transport. Because there is less surface area in contact with your skin, sweat can evaporate more freely into your mid-layer, rather than being trapped against your body. The wool fibers themselves provide contact points that actively wick moisture away, while the open-air pockets keep you from feeling clammy and cold. This system allows you to work hard and generate heat without becoming saturated with sweat, a critical advantage in sub-zero temperatures.

By creating a microclimate of warm, dry air next to your skin, wool netting offers a superior balance of warmth and breathability, making it a cornerstone of the Nordic layering system.

Shivering vs. Confusion: Which Symptom Means You Are About to Die?

In the unforgiving cold, hypothermia is a silent stalker. The most dangerous thing about it is that its most severe symptoms attack the one tool you need most for survival: your mind. While shivering is an obvious sign of being cold, it is actually a good sign. It means your body is fighting, burning energy to generate heat. The moment you should be truly terrified is when the shivering stops *without* you getting warmer. This is a signal that your body has exhausted its energy reserves and is shutting down. Your core temperature is now in a critical freefall.

As core temperature drops, the brain is deprived of oxygen and begins to malfunction. This is where the deadliest symptoms appear. You may feel a false sense of warmth, leading victims to inexplicably remove clothing (an act known as “paradoxical undressing”). More insidiously, confusion and apathy set in. You lose the ability to make rational decisions, to operate your gear, or even to recognize that you are in danger. This cognitive decline is far more lethal than the cold itself.

A useful mnemonic for recognizing these dangerous cognitive and motor skill symptoms in yourself or a partner is the “Umbles”:

- Stumbles: A loss of coordination, tripping, or difficulty walking a straight line.

- Mumbles: Slurred or slow speech, and difficulty forming coherent thoughts.

- Fumbles: A loss of fine motor skills, making simple tasks like zippering a jacket or operating a lighter impossible.

- Grumbles: A sudden, uncharacteristic shift in personality towards apathy, irritability, or belligerence.

If a person exhibits two or more of the “Umbles,” they are in a state of severe hypothermia and require immediate, aggressive rewarming and evacuation. Do not mistake these signs for simple exhaustion; while rest helps fatigue, it will only worsen hypothermia.

In the Nordic wilderness, your sharpest tool is a clear mind. Protecting it from the insidious effects of cold is your absolute first priority.

Why Cotton Is the Enemy of the Late-Season Hunter?

There is an old saying among northern woodsmen: “Cotton kills.” This is not hyperbole. In a cold, wet environment, wearing cotton is one of the most dangerous mistakes a hunter can make. Its friendly, comfortable feel in dry conditions masks a fatal flaw: its relationship with water. Cotton is a hydrophilic fiber, meaning it loves and holds onto moisture. When you sweat from the exertion of skiing or hiking, that moisture is absorbed directly into the fabric and held there.

The problem is water’s thermal conductivity. According to fabric testing data, cotton can hold up to 27 times its weight in water and loses almost all of its insulating value when wet. It actively pulls heat from your body in an attempt to evaporate the moisture, a process that can accelerate heat loss dramatically. This transforms your comfortable shirt or socks into a chilling, hypothermia-inducing compress against your skin. Wool and modern synthetics, by contrast, are hydrophobic. They repel water, wick it away from the skin, and, critically, retain a significant portion of their insulating properties even when damp.

The danger of cotton lies not just in the obvious places like t-shirts and jeans, but in the hidden details of your gear. A hunter may be diligent about wearing wool or synthetic layers but overlook the cotton in their boot laces, rifle sling, or even the webbing on their pack. These small items can become saturated with snow and moisture, creating cold spots that constantly sap your body’s warmth. Conducting a full “cotton audit” of your gear is a non-negotiable step before any winter hunt.

Your Hidden Cotton Audit Checklist

- Boot Laces: Check your boot laces. Many standard laces are cotton; replace them with durable synthetic or leather versions that won’t absorb water and freeze.

- Pack Straps: Inspect the shoulder straps and waist belt of your backpack. Some use cotton webbing or padding that can become a frozen, heat-sapping burden.

- Rifle Slings: Examine your rifle sling carefully. Many canvas or leather-backed slings have a hidden cotton core that will soak up moisture.

- Game Bags: Ditch traditional cotton game bags. Switch to synthetic mesh or other non-absorbent materials to carry your harvest.

- Stitching: Audit the thread in your clothing. Even high-tech gear can sometimes be stitched with cotton thread, creating weak points that absorb moisture.

In the calculus of winter survival, there is no room for a material that works against you. Choosing wool or synthetics is not a matter of comfort; it is a declaration of your commitment to returning home safely.

Key Takeaways

- The Nordic hunting method prioritizes slow, deliberate stalking and caloric economy over speed, embodying a philosophy of patience and resilience.

- Your survival depends on a non-cotton layering system designed for moisture management; wool mesh base layers provide a superior balance of warmth and breathability.

- You must learn to recognize the cognitive symptoms of hypothermia—the “Umbles” (stumbles, mumbles, fumbles, grumbles)—as the point of mortal danger is when shivering stops and the mind fails.

Public Land or Private Ranch: Which Destination Fits Your Skill Level?

The dream of a Nordic winter hunt is potent, but choosing the right arena is a critical decision that must be based on an honest and unflinching assessment of your skills. The difference between hunting on public land versus a privately guided ranch is not just about cost; it is a chasm in terms of the required expertise in navigation, survival, and self-sufficiency. As the renowned hunter Craig Boddington notes, “Public land demands higher skill but offers flexibility. Private/guided hunts require less logistical skill but demand a higher financial investment.”

Public land in Scandinavia offers the ultimate freedom and a true test of your abilities. You are on your own against the wilderness. This path demands expert-level skills in map reading, GPS navigation in potential whiteout conditions, and the ability to be completely self-sufficient for the duration of your hunt. There is no lodge to return to, no guide to correct a navigational error, and no one to call if your gear fails. Success is entirely dependent on your knowledge and resilience, and the success rate is highly variable.

A private, guided hunt, while expensive, provides a crucial safety net and logistical framework. It is the ideal choice for those who are still developing their winter survival and navigation skills but want to experience the hunt. The guide provides the local knowledge, the trained dogs, and the transportation. A warm lodge and meals are available, and often gear like firearms can be rented. This environment allows you to focus purely on the hunt itself, dramatically increasing the odds of success while mitigating the significant risks associated with operating alone in the arctic.

This comparative analysis from a leading Russian outfitter, summarized in the table below, clearly shows how the demands shift between these two types of hunts. According to their data from guided capercaillie expeditions, the investment in a guided hunt often correlates with a near-100% opportunity rate, a stark contrast to the uncertainties of public land.

| Factor | Public/State Land | Private/Guided |

|---|---|---|

| Navigation Skills | Expert GPS/map required | Guide provided |

| Survival Skills | Self-sufficient mandatory | Lodge support available |

| Cost | License only | $3,400-$4,400 per hunter |

| Success Rate | Variable, skill-dependent | 100% on one or more trophies |

| Equipment | Must provide all gear | Gun rental included |

Choosing the right path is the first and most important step. Be honest with yourself; the wilderness does not forgive overconfidence. An honest self-assessment ensures not only a more enjoyable and successful hunt but, more importantly, a safe one.

Frequently Asked Questions about Winter Hunting Survival

When does shivering become dangerous?

When shivering stops without warming – this signals the body has stopped fighting and core temperature is critically low. It is a sign of progression from mild to severe hypothermia and a medical emergency.

What cognitive test can detect early confusion?

Try a simple neurological test on yourself or your partner. Counting backwards from 100 by increments of 7 is a classic field test. Alternatively, try to recite your full gear list or the steps to field dress an animal in reverse order. Any hesitation or inability to perform these tasks indicates cognitive decline.

How to differentiate exhaustion from hypothermia?

Exhaustion is primarily physical and improves significantly with rest and caloric intake. Hypothermia is a systemic failure that gets progressively worse without active rewarming. A key differentiator is the presence of the “Umbles” (stumbling, mumbling, fumbling); these are clear signs of hypothermia, not just tiredness.