The debate over whether dry flies or nymphs are superior for pressured trout is a fundamental misunderstanding of the challenge.

- Success hinges not on the fly’s location in the water column, but on mastering the physics of presentation and decoding the river’s biological triggers.

- Flawless casting mechanics, drag-free drifts, and an understanding of trout bioenergetics are far more critical than simply choosing a “wet” or “dry” pattern.

Recommendation: Shift your focus from “what fly” to “why this specific presentation, in this specific location, at this exact moment” to unlock the next level of angling.

For any angler standing riverside, staring into a box brimming with meticulously tied flies, the question is as old as the sport itself: dry fly or nymph? The surface is quiet, but is that a sign of inactivity, or of fish feeding deep below? The conventional wisdom offers a simple dichotomy: if you see rises, fish a dry; if not, go deep with a nymph. This advice is not wrong, but for anglers pursuing the ultimate challenge—fooling wary, pressured trout—it is profoundly incomplete.

These selective fish, educated by countless failed presentations, are not merely feeding; they are making complex, energy-based decisions. They are connoisseurs of the current, experts in detecting the slightest unnatural drag or the faintest disturbance. To deceive them, the angler must evolve beyond a simple choice of fly and become a student of the entire aquatic system. The true art lies not in the “what,” but in the “why” and “how.” It’s an immersive discipline combining the physics of casting, the hydrodynamics of the drift, and the intricate biology of the ecosystem.

This guide moves beyond the flawed dry-or-nymph debate. Instead, it deconstructs the core scientific principles that govern success. We will analyze the mechanics of a perfect cast, the art of reading a hatch, the science of a natural drift, and the angler’s critical role as a steward of the very environment that provides this challenge. The goal is to transform your approach from one of reaction to one of deep, analytical understanding.

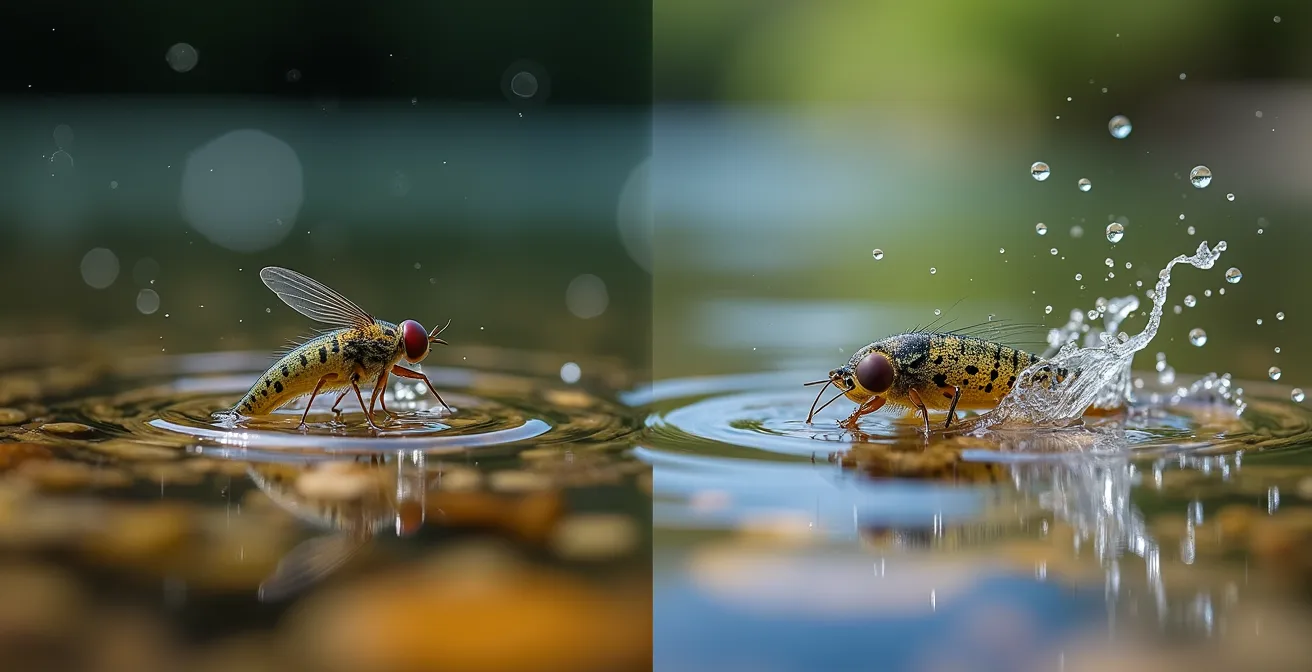

To fully appreciate the world we are about to explore, the following video offers a stunning visual immersion into the wild and scenic rivers that are the proving grounds for these advanced angling principles. It serves as a perfect backdrop to the scientific concepts discussed below.

This article is structured to build your expertise from the ground up. We will begin with the absolute foundation—your cast—and progress through reading the water, perfecting your presentation, and finally, understanding your impact on the ecosystem. Each section tackles a critical component required to fool the most selective trout.

Summary: Mastering the Science of Fooling Pressured Trout

- How to Fix the “Tailing Loop” That Knots Your Leader Every Time?

- Mayfly vs. Caddis: How to Identify the Hatch in 30 Seconds?

- Tapered Leaders: Why the Butt Section Thickness Determines Turnover?

- The Mending Technique That Keeps Your Fly Looking Natural for 10 Feet

- Strip Set vs. Trout Set: Why Lifting the Rod Loses Big Streamer Fish?

- Why Dry Hands Remove the Immune System of a Fish?

- Why Fish Congregate at the Tailout of Rapids in Summer?

- How Anglers Can Stop the Spread of Invasive Aquatic Plants?

How to Fix the “Tailing Loop” That Knots Your Leader Every Time?

Before a fly ever touches the water, the presentation is defined by the cast. The dreaded “tailing loop,” which often results in a tangled mess of “wind knots,” is not a random act of misfortune. It is a direct result of flawed physics in the casting stroke. A proper cast creates a clean, efficient transfer of energy down the line, resulting in a narrow, “U”-shaped loop. A tailing loop occurs when the rod tip travels in a concave path instead of a straight one. This happens most often when an angler applies a sudden, jerky “punch” of power, causing the line’s forward path to cross under its return path.

The solution lies in mastering smooth, gradual acceleration. Think of your cast not as a whip crack, but as painting a wall with a brush. The stroke should start slow, build speed progressively, and end with an abrupt stop to transfer the energy. Rhythmic breathing can be a powerful tool: inhaling during the backcast and exhaling during the forward cast helps maintain a relaxed, fluid motion and prevents the anxiety-driven jabs that ruin a loop.

However, technique is only part of the equation. Equipment mismatch is a frequent and overlooked culprit. Professional fly fishing instructors report that nearly 30% of tailing loop problems stem from an unbalanced setup. A common error is using a heavier fly line with a leader designed for a lighter rod, creating a “hinge effect” where the energy transfer is disrupted. The butt section of your leader must be thick enough to smoothly receive the energy from the fly line. As a rule, the leader’s butt diameter should be approximately two-thirds of the fly line’s tip diameter to ensure this seamless flow of power.

Mayfly vs. Caddis: How to Identify the Hatch in 30 Seconds?

Once your cast is perfected, the next question is what to present. For the dry fly purist, “matching the hatch” is a sacred mantra. Yet, for pressured trout, a generic imitation is insufficient. You must match the specific insect and, more importantly, its specific behavior. The two most common hatches, mayflies and caddisflies, demand entirely different presentations, and the trout’s rise form is the definitive clue to which insect is on the menu.

A mayfly hatch is a picture of grace. The insects emerge, unfurl their wings, and float serenely on the surface like tiny sailboats, waiting for their wings to dry. Trout feeding on mayflies exhibit a corresponding elegance. They will rise slowly, sip the insect from the surface film, and create a gentle, dimpling rise with concentric rings. There is no splash, no aggression—just a quiet, confident interception. In contrast, a caddis hatch is chaotic. The insects often flutter, skitter across the surface, or even dive to lay their eggs. A trout targeting caddis must be aggressive. This translates to a splashy, porpoising rise, where the fish often breaks the surface with momentum. Mistaking one for the other is a common error; presenting a dead-drifted mayfly imitation to a trout expecting a skittering caddis is a recipe for refusal.

The table below provides a quick reference for decoding these behavioral triggers on the water. Observing these subtle differences in rise forms and insect behavior is the first step in moving from simply fishing a dry fly to truly engaging in the art of entomology.

This comparative guide helps translate the visual cues on the water into an effective fly choice and presentation style. Mastering this rapid identification is crucial for success during a hatch.

| Characteristic | Mayfly Indicators | Caddis Indicators |

|---|---|---|

| Rise Form | Gentle sips, dimples on surface | Aggressive splashes, porpoising |

| Adult Behavior | Float serenely after hatching | Skitter, flutter, or dive |

| Pre-hatch Signs | Nymphs migrating to shallows | Increased caddis cases drifting |

| Presentation Style | Dead drift required | Twitching often effective |

Tapered Leaders: Why the Butt Section Thickness Determines Turnover?

The tapered leader is one of the most critical yet misunderstood components in fly fishing. It is not merely a connection between the thick fly line and the delicate fly; it is the transmission system for all the energy generated in your cast. Its sole purpose is to continue the smooth dissipation of energy so that the fly lands gently and accurately. The success of this energy transfer is almost entirely dependent on one factor: the diameter of the leader’s butt section.

If the butt section is too thin relative to the fly line, it creates a “hinge.” Energy cannot flow smoothly from the thicker, heavier line to the abruptly thinner leader. This causes the loop to collapse, the leader to fail to straighten, and the fly to land in a pile. Conversely, if the butt section is too stiff, it carries too much energy, causing the fly to “kick” or slap the water. Research on leader dynamics shows that a mismatch of more than 0.005 inches can lead to a 60% reduction in casting accuracy. For pressured fish, this is the difference between a take and a refusal.

A reliable formula for matching line to leader is to multiply the fly line weight by 0.0042. For a standard 5-weight line, this yields an ideal butt diameter of 0.021 inches. This ensures the leader’s mass is substantial enough to accept the energy from the fly line without collapsing. Anglers should then adjust based on conditions. On windy days, increasing the butt diameter by 0.002 inches provides more power to punch through the wind. For the most delicate presentations of tiny dry flies, decreasing it by 0.002 inches allows for a softer landing. Thinking of your leader as a simple piece of monofilament is a mistake; it is a precision-engineered tool for managing energy.

The Mending Technique That Keeps Your Fly Looking Natural for 10 Feet

Once your perfectly chosen fly, delivered by a perfectly balanced leader, lands on the water, the battle against physics has only just begun. The river’s complex currents immediately conspire to pull and tug at your fly line, creating unnatural drag. For a selective trout, even the slightest hint of drag is a blaring alarm that something is wrong. The key to a long, natural drift is mastering the mend—specifically, the reach mend.

A standard mend is performed after the line is already on the water. It involves lifting the rod and flipping a curve of line upstream to counteract the downstream pull of the current. While effective, this action creates surface disturbance that can alert a wary trout. The reach mend, however, is an aerial maneuver executed before the line touches the water. As the forward cast unrolls, the angler “reaches” the rod tip either upstream or downstream, placing an initial curve in the line as it lands. This pre-set curve acts as a buffer, allowing the fly to drift naturally for a significant distance before drag even begins to set in.

The effectiveness of this technique on pressured waters is profound. According to an analysis by professional guides, implementing the reach mend increases hookup rates by as much as 40% on heavily fished rivers. Advanced anglers take this a step further, employing “micro-mends” throughout the drift. These are tiny, subtle movements of the rod tip, often just a few inches, that adjust the leader’s position without disturbing the main fly line. This continuous management of hydrodynamics allows the fly to behave exactly like a natural insect, free from the invisible leash of the line.

Strip Set vs. Trout Set: Why Lifting the Rod Loses Big Streamer Fish?

The moment of the take is the culmination of all your effort. A fish commits, and in a split second, you must set the hook. Yet, this is where many anglers, particularly those transitioning from nymph or dry fly fishing, make a critical error when fishing streamers. They react with a “trout set”—a reflexive, upward lift of the rod. While effective for small flies, this action is the primary reason big fish are lost on big flies.

The physics are simple. A trout set pulls the hook upward, often harmlessly out of the fish’s mouth, especially if the fish is turning. The rod, with its inherent flex, acts as a shock absorber, dampening the force needed to penetrate a tough, bony jaw. The strip set, by contrast, is a direct application of force. Instead of lifting the rod, the angler pulls sharply on the fly line with their non-casting hand while keeping the rod tip low and pointed at the fish. This creates a straight-line connection, driving the hook point directly into the fish’s jaw with maximum power.

The difference in effectiveness is not marginal; it is dramatic. Understanding the right application for each hook set is fundamental to landing the fish you are targeting.

This table from a comparative analysis of hook set physics clearly illustrates why the strip set is superior for large, predatory fish that attack streamers with force.

| Factor | Strip Set | Trout Set |

|---|---|---|

| Hook Direction | Straight line into jaw | Upward pull out of mouth |

| Success Rate (Large Fish) | 85% hookup retention | 45% hookup retention |

| Best Application | Streamers, large flies | Dry flies, small nymphs |

| Line Control | Maintains tension during turn | Creates slack on rod lift |

Why Dry Hands Remove the Immune System of a Fish?

The successful catch of a pressured trout is a moment of triumph, but it is also a moment of profound responsibility. The ethos of catch-and-release is predicated on returning the fish to the water unharmed, yet many well-intentioned anglers unknowingly inflict a fatal injury. The single greatest threat to a released trout is being handled with dry hands. This seemingly innocuous act is akin to stripping away the fish’s entire immune system.

A fish’s body is covered in a protective layer of slime. This is not just mucus; it is a complex biological shield rich in glycoproteins, antibodies, and antimicrobial enzymes. This slime coat is the fish’s primary defense against a hostile aquatic environment teeming with bacteria, fungi, and parasites. When you touch a fish with dry hands, you strip off this vital layer. The damage is immediate and often invisible. Research shows that fish with compromised slime coats can suffer from osmotic shock within 24-48 hours, leading to delayed mortality even if they swim away strongly.

The statistics are sobering. Rigorous conservation research demonstrates a 73% increase in post-release mortality when fish are handled with dry hands for more than 10 seconds. The solution is simple but non-negotiable: always wet your hands thoroughly before touching a fish. This minimizes the removal of the slime coat. Better yet, use a rubber net and keep the fish in the water as much as possible, handling it for the briefest possible moment. A quick photo is not worth the life of the animal. As purists and conservationists, our goal is not just to catch the fish, but to ensure its survival long after the release.

Why Fish Congregate at the Tailout of Rapids in Summer?

Understanding where a trout lives is as important as understanding what it eats. An angler can have a perfect cast and the perfect fly, but if they are fishing in empty water, the effort is wasted. During the warm summer months, one of the most productive and predictable places to find trout is in the tailout of a rapid—the calmer, deeper water just downstream from the turbulence. This is not a random preference; it is a calculated decision based on the principles of bioenergetics.

A trout’s life is a constant balancing act between energy expenditure and caloric intake. They seek to position themselves where they can consume the maximum amount of food with the minimum amount of effort. Tailouts provide the perfect combination of three key factors:

- Oxygen Concentration: The churning, turbulent water of the rapids infuses the water with dissolved oxygen. This highly oxygenated water flows directly into the tailout, creating a refuge for trout when high water temperatures elsewhere in the river reduce oxygen levels.

- Food Conveyor Belt: The same powerful currents that oxygenate the water also act as a food delivery system. The rapids dislodge nymphs and other aquatic insects from the riverbed and funnel them directly into the holding lies in the tailout. A trout positioned here can intercept a steady stream of food without having to move.

- Predator Confusion: The broken, turbulent surface of the rapid provides excellent overhead cover from avian predators like ospreys and herons, while the fish itself can hold in the clearer, slower water below, easily spotting incoming food.

In essence, the tailout is a trout’s prime real estate. It’s a low-energy living situation with a high-volume food delivery service and excellent security. By learning to identify these specific locations—the seam between fast and slow water, the deep slot behind a boulder—the angler can stop guessing and start targeting fish with scientific precision.

Key Takeaways

- The “dry vs. nymph” debate is a false choice; mastering the physics of presentation is what convinces pressured fish.

- A trout’s behavior is driven by bioenergetics—they will always be where they can get the most food for the least energy.

- Ethical angling is not just a philosophy, but a scientific practice, from proper fish handling to preventing the spread of invasives.

How Anglers Can Stop the Spread of Invasive Aquatic Plants?

The ultimate expression of angling purism is the commitment to protect the resource for future generations. The single greatest long-term threat to our wild trout fisheries is not overfishing or pollution, but the silent invasion of non-native aquatic species. Plants like Didymo (“rock snot”) and Eurasian watermilfoil can completely transform a river’s ecosystem, altering water temperature, choking out native vegetation, and collapsing the insect populations that trout depend on for survival. Anglers, as the individuals who travel most frequently between watersheds, are unfortunately the primary vectors for this spread.

However, this also means we are the first line of defense. The responsibility to prevent the spread of these invasive species rests squarely on our shoulders. Microscopic plant fragments and spores can hide in the felt soles of wading boots, in the core of a fly line, or even within the materials of a woolly bugger. Adopting a strict decontamination protocol is not optional; it is an ethical imperative. The “Clean, Drain, Dry” method is the gold standard for preventing the transport of these harmful organisms from one body of water to another.

Being a steward of the environment is an active role. It requires diligence after every trip and a commitment to educating fellow anglers. By taking these simple but critical steps, we can ensure that the pristine ecosystems we cherish remain healthy and vibrant for the anglers who will follow in our footsteps.

Your Action Plan for Preventing Invasive Species Spread

- Inspect & Clean: Thoroughly inspect all gear, including wader seams, boot laces, and even the materials on your flies. A resource like this guide on trout fishing fundamentals often includes conservation best practices. Clean away any visible mud, plants, or debris.

- Apply the Protocol: Meticulously follow the “Clean, Drain, Dry” procedure. Clean all equipment with hot water (at least 140°F / 60°C) if possible. Completely drain every item that can hold water. Finally, allow all gear to dry completely for a minimum of 48 hours before entering a new watershed.

- Identify & Report: Use smartphone apps like iNaturalist or your local wildlife agency’s reporting tool. If you see a plant or animal you don’t recognize or suspect is invasive, photograph it and report its location to the proper authorities.

- Understand the Impact: Educate yourself on the specific threats in your region. Knowing that an invasive plant can decimate mayfly populations provides powerful motivation for following decontamination protocols.

- Lead by Example: Talk to other anglers at the boat ramp or on the riverbank. Share your knowledge about invasive species and demonstrate your commitment to cleaning your gear. Stewardship is contagious.

The journey from novice to expert is not measured in the number of fish caught, but in the depth of understanding gained. The question is never simply “dry fly or nymph?” The real questions are: what are the physics of my cast? What is the biological story the river is telling me? How can I present my fly as a natural, seamless part of that story? And finally, how can I leave this place better than I found it? The next time you stand before the water, approach it not just as an angler, but as a scientist and a steward. That is the path to truly mastering the art.